Skewed loss of language capabilities from semantic dementia

Posted on July 15, 2023. Tags: randomNote: This was a term paper that I wrote for a psycholinguistics course I took at Brown (CLPS 0800) under Prof. James Morgan. I thought the material was very interesting, so I decided to repost my work here. I have no background in linguistics, so all mistakes here are my own.

Background

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a rare neurodegenerative disease, affecting less than 50,000 individuals in the United States (GARD). It leads to loss of certain language capabilities, while other skills and episodic memories (NAA) remain mostly intact. This allows PPA to be contrasted with other manifestations of dementia such as Alzheimer’s disease, which may involve a more holistic loss of function across the board (Kertesz 714).

Depending on the specific parts of language lost, patients are roughly divided into three variants of PPA: non-fluent, logopenic, and semantic. Semantic variant primary progressive aphasia, known more simply as semantic dementia, is particularly interesting in that patients gradually forget parts of their vocabularies over time, but retain the ability to speak fluently in well-articulated, grammatical sentences (Kertesz 711). It thus offers a unique opportunity to study the nature of the mental lexicon, decoupled from other confounding stages of language production and comprehension such as speech planning and connections to knowledge and memory – which may be broadly impacted in patients suffering from other dementias.

With semantic dementia, loss of language capabilities is skewed – that is, some parts of language deteriorate faster than others. In particular, knowledge of nouns typically is lost earlier than knowledge of verbs, suggesting differences in the ways in which words are stored by the mental lexicon, with some being in a sense more durable and damage-resistant than others. Grammar and sentence structure are spared, as is the ability to pronounce and articulate speech fluently. Finally, the patterns of language loss in multilingual patients reflect those of monolingual patients, while also revealing that multiple languages do not enjoy equal support by the lexicon, with some being lost at a faster rate than others.

Nouns are lost faster than verbs

At the individual word level, vocabulary is not lost from all categories at a uniform rate; rather, generally nouns – particularly those describing concrete objects as opposed to abstract concepts – are lost before verbs and function words.

Two studies of this phenomenon

Indeed, most of the patients participating in Silveri et al.’s investigation of the impact of semantic dementia demonstrated greater deterioration of nouns than verbs (Silveri 1000). Losses of words were measured using a picture naming task, in which patients were asked to produce a word describing the object or action in an image. A potential criticism I had of this technique is that single-word retrieval is not necessarily reflective of connected speech, since it does not use the same planning, priming, or activation pathways that speaking in full sentences does. Because of this, single-word retrieval may more frequently result in tip-of-the-tongue state (as described in Sedivy 10.2).

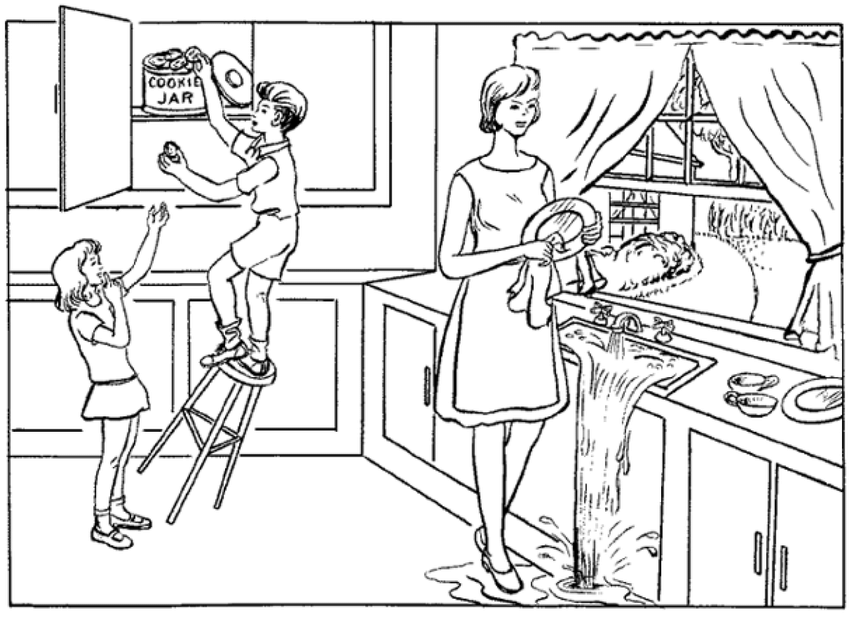

The image used as stimulus in Bird et al.’s “cookie theft” task.

The image used as stimulus in Bird et al.’s “cookie theft” task.

However, this criticism was addressed by Bird et al., who reached similar results using the “Cookie Theft” task, in which participants are asked to describe (in a conversational fashion) what is happening in a scene. Despite the task being far less constrained than picture naming, a similar pattern of reduction in noun usage occurred (Bird 44).

On top of the differential loss of words depending on grammatical category, Silveri et al. found that nouns for natural objects deteriorated earlier than man-made objects. Furthermore, they found that nouns for most concrete items deteriorate earlier than words for abstract concepts such as numbers (Silveri 1002). In my opinion, this finding seems to call into question both Silveri’s and Bird’s methods for measuring degradation of nouns versus verbs. In both experiments, participants were given images as a stimulus and asked to elicit speech in response. However, images by nature are limited to capturing visible, physical objects; thus, these tasks are biased towards naming of concrete items. As a result, lower performance in producing nouns in the two experiments may not necessarily be indicative of deterioration of noun knowledge as a whole.

Is faster deterioration of nouns just a statistical mirage?

Though Bird and Silveri concurred that some words are lost faster than others, they disagreed on the root cause of the phenomenon. Bird et al. made a purely statistical argument: taking Cookie Theft speech from control participants without semantic dementia, they substituted out specific words that occur in low frequencies for more general alternatives. They found that the noun/verb and content word/function word ratios of this model at different frequency cutoffs closely mirrored the speech of semantic dementia patients at various stages of the disease (Bird 37). This led them to the conclusion that loss focused in particular categories of words over others may be simply a result of different usage frequencies of those words rather than greater physical degradation of one category over another. Specifically, verbs are generally used more frequently and in broader contexts than specific nouns, so they are retained better in semantic dementia.

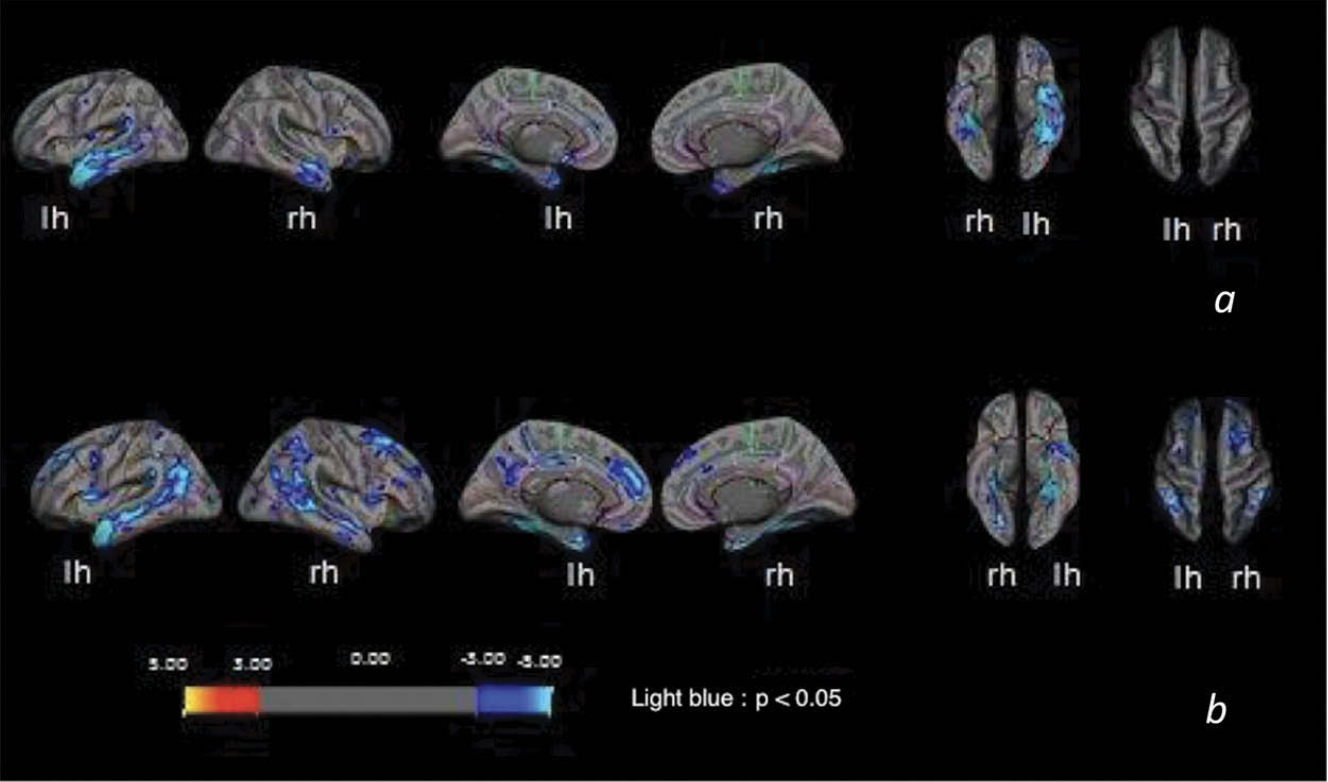

Brain scans of patients with semantic dementia. Note the concentration of

atrophy in the language-processing regions of the left hemisphere. Credit:

Silveri et al.

Brain scans of patients with semantic dementia. Note the concentration of

atrophy in the language-processing regions of the left hemisphere. Credit:

Silveri et al.

In contrast, Silveri et al. found via brain scans that patients with particularly disproportionate loss of nouns compared to verbs had atrophy of brain tissue limited to the left temporal lobe, while patients with less disproportionate loss in the two categories showed much broader-scale damage to the parietal and frontal lobes as well (Silveri 1002). This suggests that parts of the mental lexicon are indeed physically separated in the brain into specialized units.

From this result I would hypothesize that the left temporal lobe may store primarily noun information instead of verbs, and thus damage concentrated in that area would affect nouns more heavily than verbs. The reality of the situation is likely more nuanced than that, and I think that the two hypotheses can coexist. For example, Silveri et al. noted that patients showed greater deterioration of semantic knowledge of natural objects before man-made objects and body parts yet admitted that the patterns of atrophy in patients who showed this difference to varying degrees were not obviously distinguishable (Silveri 1001). But this can be explained by Bird’s hypothesis, since we encounter and speak of laptops and other man-made items more frequently in everyday life than whales and zebras. Additionally, Bird et al. found a significant negative correlation between imageability and frequency (words that are less visualizable tend to be more frequently used), which helps explain Silveri’s findings that words for concrete items are lost before abstract concepts.

Zooming out from words to sentences

The lexicon does more than store vocabulary; among other roles, it also holds information on syntactic categories of words and how the meanings of words may change depending on the sentence context. For example, the meanings of verbs are highly connected to the argument structures they take part in (Sedivy 5.4). Based on this, it is fair to postulate that the lexicon is intimately connected with grammatical understanding. It is therefore surprising to me that grammar is preserved in patients with semantic dementia despite the deterioration of their lexicons.

Grammar itself is an abstract concept, not a visible metric, but its preservation can be quantified through two complementary lenses: speech production and sentence comprehension.

Preservation of grammar from a generating point of view

On the speech production side, Meteyard et al. transcribed and compared speech samples of semantic dementia patients and healthy controls. On the word-by-word level, their results comport with the conclusions of Bird et al., with patients showing a marked decrease in usage of low-frequency nouns and verbs, substituting in broader pronouns and passive pronouns instead (Meteyard 22). Overall, Meteyard et al. found that semantic dementia patients’ speech contained no major syntactical errors, suggesting that patients understand what correct grammar is and continue to be able to apply those rules in their own speech.

There are some differences in the speech patterns between patients and controls; for example, patients tend to use prepositional phrases more frequently. The authors assert that this is due to patients relying on highly frequent prepositions and Wh words more, which results in increased use of clauses which involve these words (Meteyard 26). I find this to be a reasonably strong explanation; for example, the man with the hat avoids the less frequent present participle in the man wearing the hat – and happens to contain a prepositional phrase. Furthermore, patients produce fewer relative clauses and other modifications that make sentence structures more complex. Meteyard thus concludes that usage of low-frequency syntax structures is lost over time in parallel with deterioration of low-frequency words (Meteyard 28).

While the study undeniably proves preservation of some grammatical understanding in semantic dementia patients, it has several weaknesses. In transcribing the speech, the authors discarded partially formed phrases, and if speakers attempted the same phrase twice, the authors always chose the correct attempt of the two – regardless of whether it was spoken first or second. I believe that some true errors produced by patients would have been lost at this stage, and that attempting a phrase twice may be indicative of a level of syntactical uncertainty that could have been interesting to explore.

Furthermore, the unconstrained nature of the prompt they used to collect the speech samples, simply asking the subjects to describe a memory of their lives, gave subjects plenty of leeway in terms of the speech they produce. In other words, it is hard to disambiguate whether the reduction in frequency of certain grammatical constructions is due to patients truly forgetting them, or if they are simply avoiding those constructions because they lack the words utilized in those constructions. To determine if they still understand these constructions, it is necessary to turn to the other method of testing grammatical understanding, sentence comprehension.

Preservation of grammar from a comprehending point of view

Rochon et al. performed a longitudinal case study of a semantic dementia patient, referred to as AK, in which they monitored her ability to spot grammatical errors and comprehend sentences over a period of five years. The deterioration of her semantic knowledge over time was evident, with her scores on vocabulary and oral reading tasks dropping precipitously over the five-year period (Rochon 319). Yet her ability to discriminate between sentences of correct and incorrect grammar only dropped slightly, and she performed at near-control accuracy until the last year of the study (Rochon 320), in which she was no longer able to understand the instructions for the task.

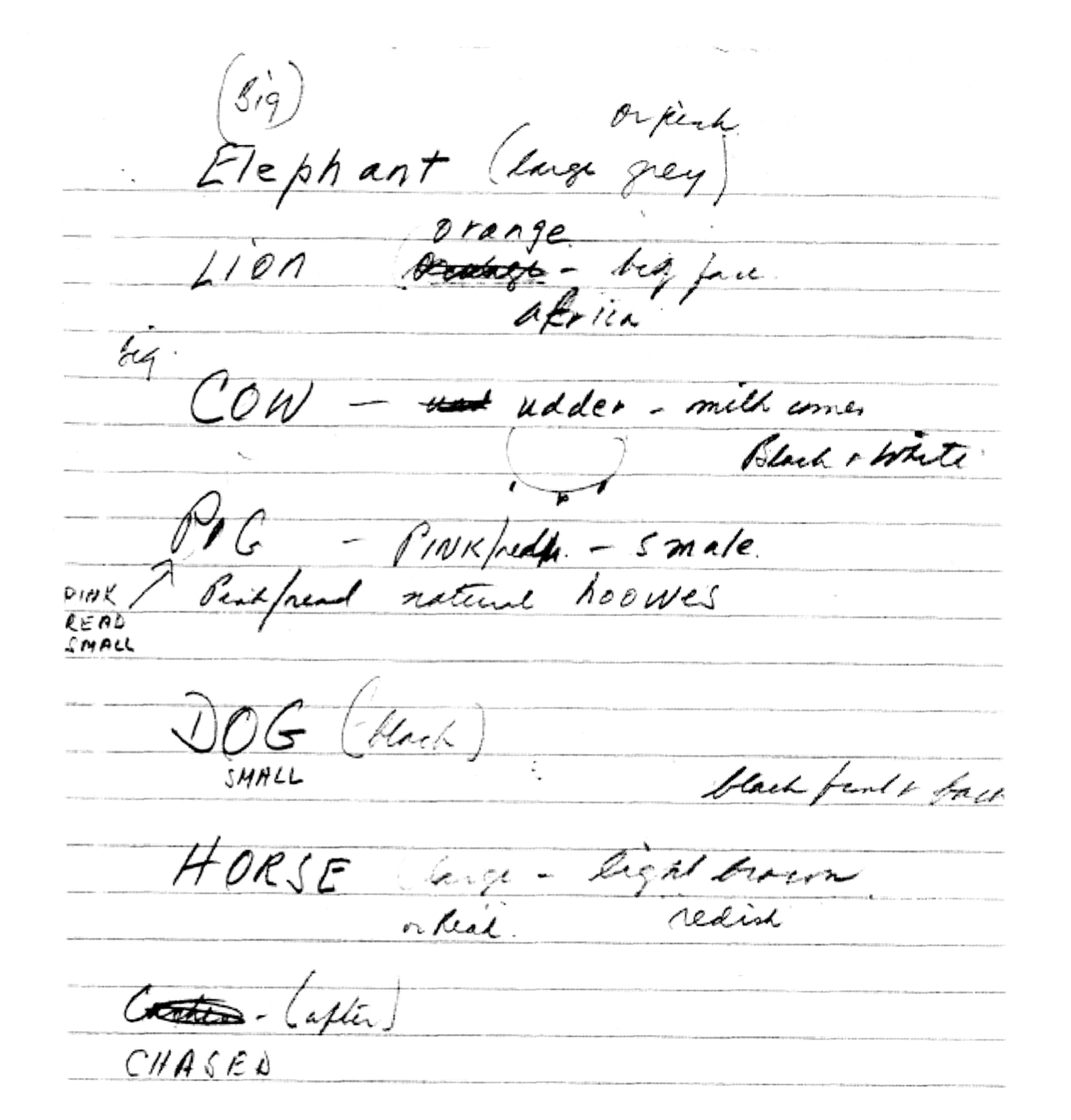

AK’s notes to help herself remember what

“lions”, “dogs”, etc. were. Note her reliance on colors, likely easier to

remember due to daily exposure à la Bird et al.

AK’s notes to help herself remember what

“lions”, “dogs”, etc. were. Note her reliance on colors, likely easier to

remember due to daily exposure à la Bird et al.

In fact, AK was not just using statistical knowledge or rulesets to guess whether a sentence had valid grammar or not; she remained capable of genuinely comprehending a wide variety of sentence structures. To show this, Rochon et al. employed a picture matching task where images were corresponded with sentences with subtle changes in structure and meaning (e.g., The pig chased the lion has the same meaning as The lion was chased by the pig, despite the reversal of noun positions). Despite AK eventually forgetting the meanings of the words themselves in the sentences (having to write notes to herself describing what a lion, a pig, or the action of chasing was), she performed exceedingly well at the task, even above the average control accuracy (Rochon 322). Although the sample size is small, and different patterns of brain atrophy will undoubtedly yield different results in other patients, this is strong evidence that grammar is preserved in semantic dementia even with the deterioration of single-word categories, at least before the disease progresses to a more holistic loss of function.

How can we connect the two POVs?

Both Meteyard and Rochon agree that there is a great degree of syntactical knowledge that is preserved in patients with semantic dementia. However, at first glance the inferences that can be made from the two results seem at odds with each other.

In Meteyard et al.’s case, it appears that grammar and the lexicon are inextricably linked; forgetting words also leads to a loss of diversity in syntactical constructs that patients use in sentences. Here, the lexicon appears to play a key role, supplying information on how specific words should be used in different ways. On the other hand, Rochon’s study of AK showed that grammar and the lexicon are relatively separate modules, such that syntactical knowledge can exist and be utilized even in the absence of words. Together, the I feel that the two results suggest that while this knowledge may be preserved in patients, it is a one-way connection. Patients can understand certain syntactical constructs, but those constructs are otherwise “locked” to them; they do not know how to access and apply it in their own speech.

Case studies on multilinguals

Semantic dementia in multilinguals is another fascinating area to explore.

An English-Catalan-Spanish trilingual

The pattern of language deterioration in multilinguals shares many similarities with monolinguals, as documented by Calabria et al. in their longitudinal study of an English-Catalan-Spanish trilingual, TC.

Like the patients in Bird et al.’s study, TC had difficulty recalling infrequently used words (Calabria 249), and the loss of vocabulary was most pronounced in Spanish, the language she used least frequently in her daily life. This provides further evidence that frequent use of words is key to long-term retention in semantic dementia, whether by strengthening redundant connections in the brain or by continuous relearning as old connections are lost. Like the subjects in Silveri’s study, TC’s knowledge of numbers in both English and Catalan was highly conserved, making few mistakes in naming tasks (Calabria 256). And finally, like AK from Rochon et al.’s study, TC’s grammatical understanding remained fairly constant over the course of the study in all three languages.

Curiously, Calabria et al. found they were able to predict which words were lost from TC’s Catalan vocabulary through errors in English tests, indicating that in some cases, it is not the word forms themselves which are lost, but rather the shared underlying semantic representation. This effect did not show up with Spanish, suggesting that it is still possible to lose vocabulary without losing the underlying meaning.

Furthermore, despite being more comfortable speaking Catalan, English – TC’s native language – appeared to enjoy some special treatment. TC struggled to translate words from English to Catalan or Spanish, but not the other way around. Since she acquired Catalan and Spanish later in life (after eighteen years of age), I would guess this is related to the fact that the languages were initially learned via their translations to English, and thus it remains more natural for her to translate from Catalan to English.

Additionally, TC also performed better with English than Catalan in other naming tasks. From this, it appears that age of acquisition plays a role in retention, separately from frequency of use.

This conclusion would be challenged by Ellajosyula et al., who studied loss of single-word vocabulary in bilinguals.

Bilinguals with semantic dementia in India

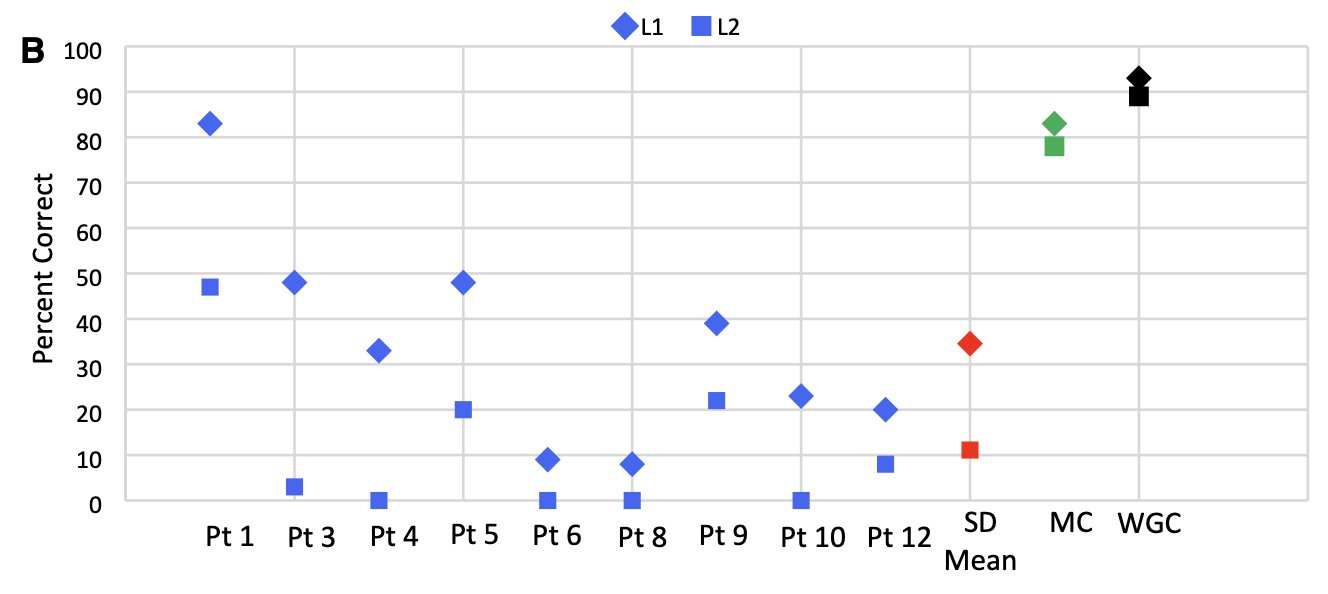

In their study of sixteen bilinguals with semantic dementia (a far greater sample size than the single individual in Calabria’s study), they found that in all cases, the language that the patients were most proficient in before the onset of disease was the one that was best retained (Ellajosyula 556).

Accuracy scores of SD patients in naming tests. The diamond is their most

proficient language, and the square is their second most proficient language.

Accuracy scores of SD patients in naming tests. The diamond is their most

proficient language, and the square is their second most proficient language.

Most striking to me is the case of Patient 12, whose most proficient language was Hindi, acquired at age 9 (Ellajosyula 554) – also a relatively late age of acquisition. Despite this, they retained knowledge of Hindi better than Tamil, their native tongue.

However, I believe Ellajosyula et al.’s paper has some weaknesses, particularly in the way proficiency was measured. Pre-onset proficiency was simply a score given by patients (or their caretakers) based on their best estimates; this anecdotal metric seems easily biased, as better current performance in a language may cause patients or caretakers to mistakenly believe that that language was always more proficient.

Between the small sample size in Calabria’s study and the non-rigorous proficiency measurements in Ellajosyula’s study, the effect of native versus non-native language acquisition on retention in semantic dementia remains unclear.

Conclusion

In patients with semantic dementia, knowledge of individual words deteriorates at varying rates depending on frequency of use and the extent of atrophy in the brain, thus suggesting a lexicon with many redundant and highly preserved connections that may be distributed in different areas of the brain, depending on speech. Syntactical knowledge is generally conserved despite the loss of vocabulary, leaving patients capable of comprehending more complex sentence structures than they can produce in speech. This hints that grammatical understanding is a modular, partially dependent process from lexical knowledge, and can withstand atrophy of vocabulary-storing regions of the brain. Finally, deterioration patterns from multilingual patients mirrors that of monolingual patients and helps reinforce the model of one shared lexicon across multiple languages.

Sources

GARD. “Primary Progressive Aphasia.” Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Feb. 2023, https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/8541/primary-progressive-aphasia.

Sedivy, Julie. Language in Mind, Second Edition. Sinauer Associates, 2020.

NAA. “Primary Progressive Aphasia.” National Aphasia Association, 30 Mar. 2022, https://www.aphasia.org/aphasia-resources/primary-progressive-aphasia/.

Kertesz, Andrew, et al. “Primary Progressive Aphasia: Diagnosis, Varieties, Evolution.” Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, vol. 9, no. 5, 2003, pp. 710–719., https://doi.org/10.1017/s1355617703950041.

Silveri, Maria Caterina, et al. “What Is Semantic in Semantic Dementia? the Decay of Knowledge of Physical Entities but Not of Verbs, Numbers and Body Parts.” Aphasiology, vol. 32, no. 9, 2017, pp. 989–1009., https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2017.1387227.

Bird, Helen, et al. “The Rise and Fall of Frequency and Imageability: Noun and Verb Production in Semantic Dementia.” Brain and Language, vol. 73, no. 1, 2000, pp. 17–49., https://doi.org/10.1006/brln.2000.2293.

Meteyard, Lotte, et al. “Ever Decreasing Circles: Speech Production in Semantic Dementia.” Cortex, vol. 55, 4 Mar. 2013, pp. 17–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2013.02.013.

Rochon, Elizabeth, et al. “Sentence Comprehension in Semantic Dementia: A Longitudinal Case Study.” Cognitive Neuropsychology, vol. 21, no. 2–4, 2004, pp. 317–330, https://doi.org/10.1080/02643290342000357.

Calabria, Marco, et al. “Multilingualism in Semantic Dementia: Language-Dependent Lexical Retrieval from Degraded Conceptual Representations.” Aphasiology, vol. 35, no. 2, 2019, pp. 240–266, https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2019.1693025.

Ellajosyula, Ratnavalli, et al. “Striking Loss of Second Language in Bilingual Patients with Semantic Dementia.” Journal of Neurology, vol. 267, no. 2, 2019, pp. 551–560, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09616-2.