Studying Chinese

Posted on June 4, 2023. Tags: anki, chineseI am keenly aware that as I get older, picking up new languages is only going to become harder and harder. I am probably already past the sensitive period for language acquisition, and I have relatively more free time now when school is on break than I might ever have again when I am living on my own. Because of this, learning Mandarin Chinese (the language of my parents, my relatives, and the culture I grew up with) is more of a priority for me at this time.

After some trial and error, I have found the most effective way for me to study Chinese, one that I have been using for about a year now and actually feel tangible improvements from using.

I am a “second generation” immigrant; my parents are Chinese, but I was born and raised in America. Aside from a scant few years in my community’s Chinese school, I have not received any formal Chinese schooling. Although I speak Chinese at home, I am not regularly exposed to written Chinese – all signs, product packaging, and media surrounding me are obviously in English.

As such, there is a large disparity between my speaking proficiency versus my reading and writing proficiency. I have no trouble linking sounds to meanings, so my study strategy focuses on linking written forms to sounds. This requires a lot more effort with Chinese than in alphabetic languages like Korean or Russian, because Chinese is a logographic writing system; there’s no way to reliably “sound out” or “guess the spelling” of words. This strategy also may not be as applicable to those starting out learning Chinese from scratch.

I have tried languages apps like Duolingo, and found them not suitable for my purposes since I do not need to learn speaking, grammatical constructs, or basic vocabulary again. I only need to “bootstrap” my reading and writing literacy from my listening and speaking knowledge, and I have landed on Anki as the best solution to do so.

My Chinese-studying process occurs in three broad phases: collecting, storing, and reviewing. It is more of a pipeline than an iterative loop in the sense that all three stages are happening at the same time, with new terms being added continuously and moving through the three phases.

Collecting

The first step in the process is to collect new terms into a list of things to learn. In the beginning, I could collect new vocab easily, just by looking up very common words that I use daily but did not know how to write (e.g. 可以, 需要). I would make a haphazard list in the Notes app on my phone of such phrases to learn.

Now, I rely on reading Chinese material to find words to learn. At first, I read through a bit of 父亲与果园, a short story by 李云雷. While this was extremely effective in finding new vocabulary, it was also much too difficult. I would run into sentences packed from beginning to end with words that I was completely unfamiliar with and had no clue how to apply even in spoken Chinese.

The first page of 父亲与果园.

The first page of 父亲与果园.

I have found The Chairman’s Bao to be a much gentler source of words. I find a lot of new nouns that I don’t use in my daily life (e.g. 宜家 – IKEA), and TCB has a convenient save function so I don’t have to maintain a list outside of the app. I also come across conjunctions, adverbs, and adjectives that I can’t read, although it’s typically the case that I know what they sound like (e.g. 顺便 – conveniently, simultaneously). When I tap on the word, TCB shows me its pinyin, which is generally enough for me to understand it, save it, and move on.

I generally read at most 2 articles on TCB a day; while this is a blisteringly slow pace, I have other things to do in life, and I worry that by reading more I would be introducing new terms at an unsustainable pace.

Storing

In the collecting phase, I built up a list of new vocab words that I need to learn how to write. In the storing phase, I build these terms into my growing Anki deck for review.

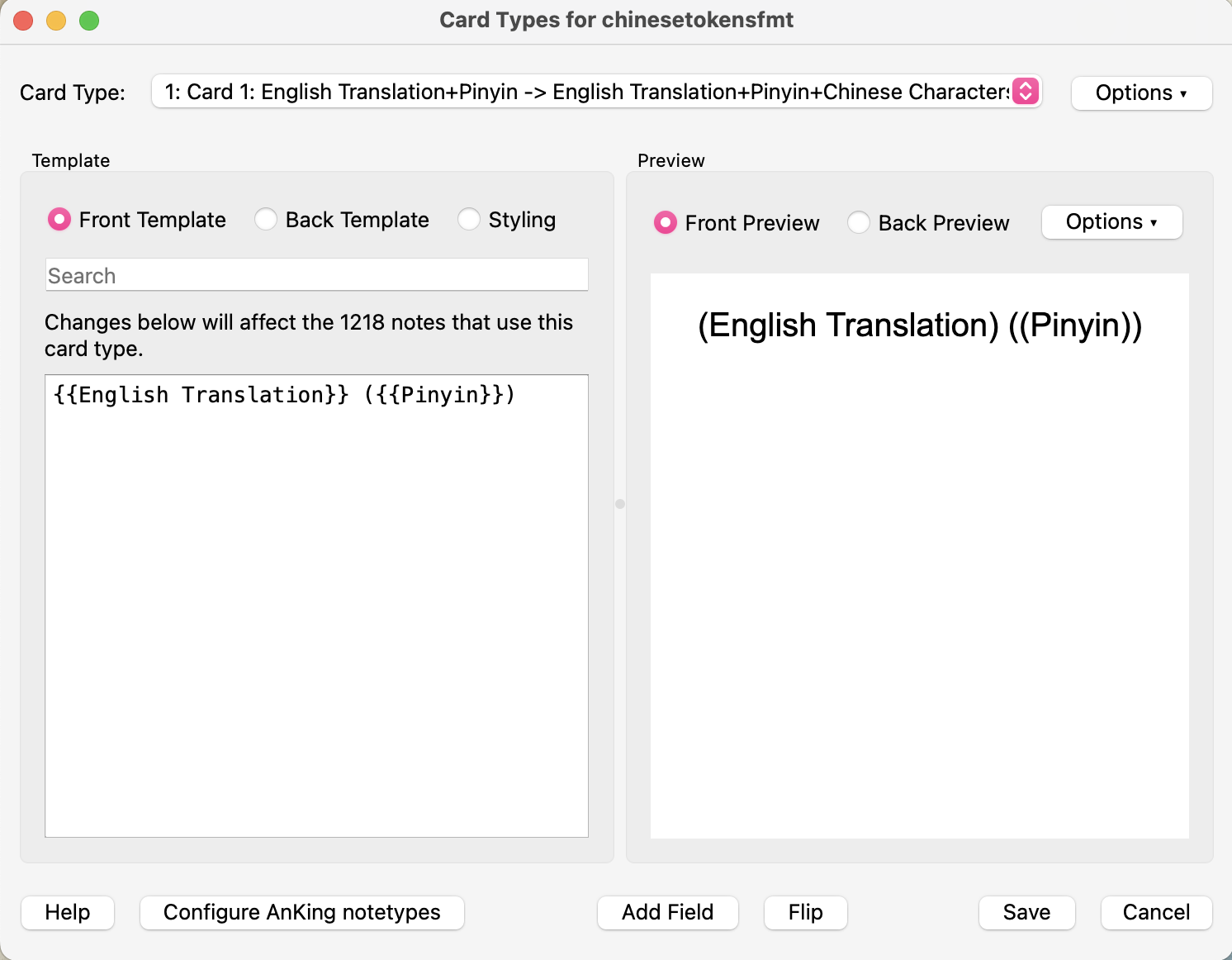

Anki card format

Again, my focus is linking written Chinese to their sounds. However, pinyin can frequently be ambiguous. For example, 家, 加, 嘉, and 佳 are all pronounced “jiā”. To help disambiguate these cases, I include both the English definition and pinyin on one side of a flashcard, and put the Chinese character on another. An added benefit is I also reinforce connections between the Chinese character and its English translation.

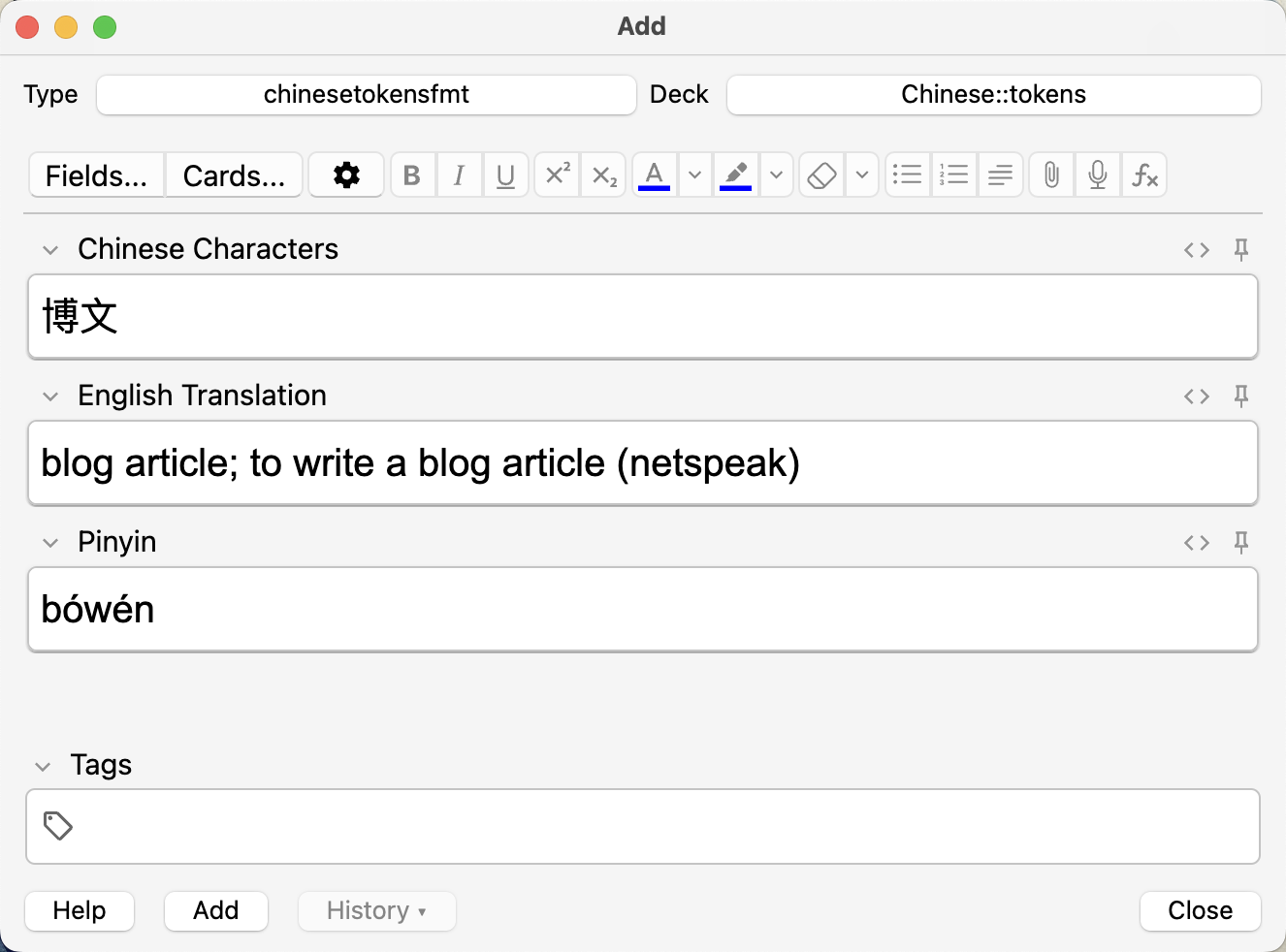

To ease the flashcard creation process, I created a custom card format called

chinesetokensfmt. It has three fields: English Translation, Chinese

Characters, and Pinyin.

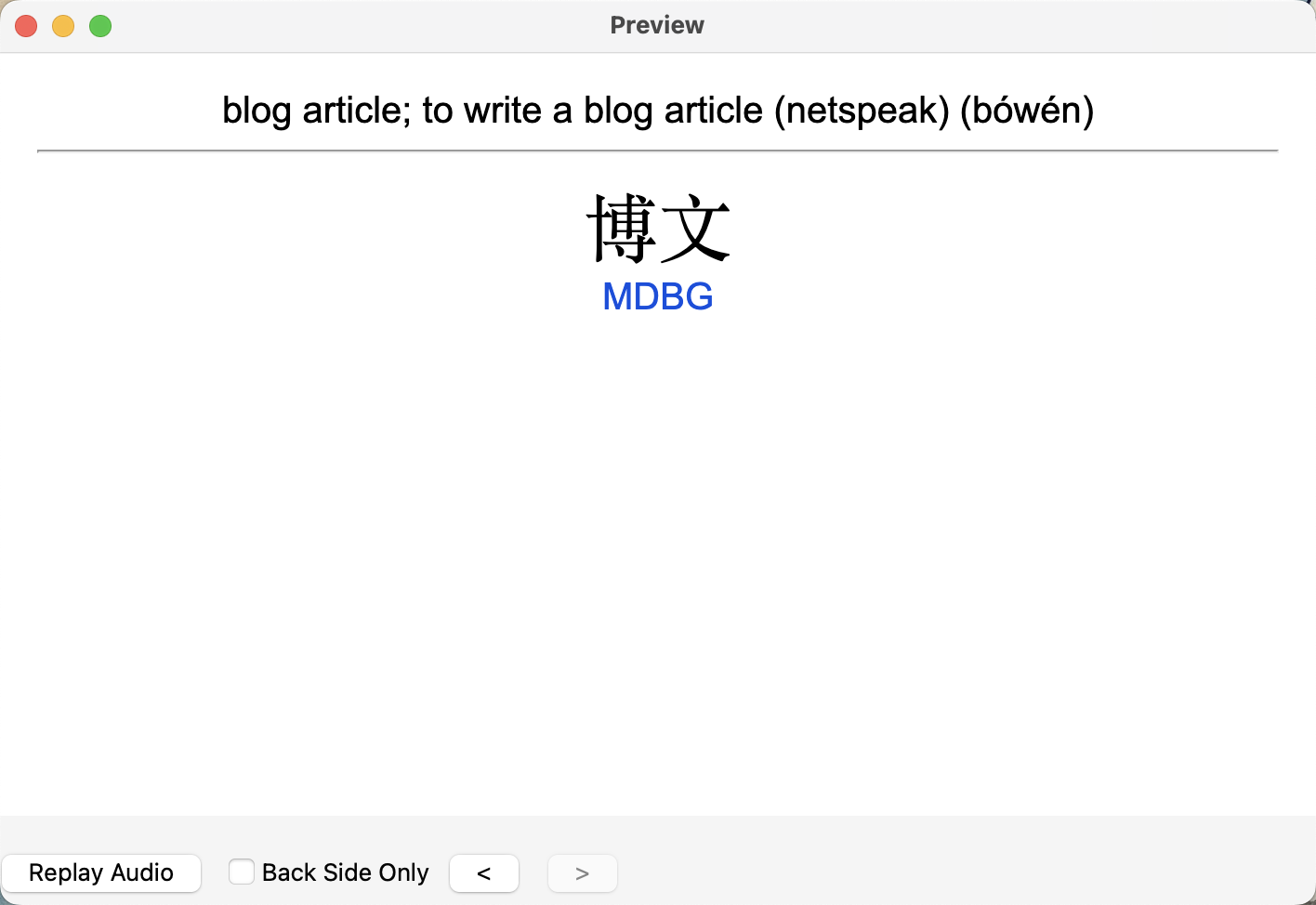

The card front format. The English definition and pinyin are displayed

together.

The card front format. The English definition and pinyin are displayed

together.

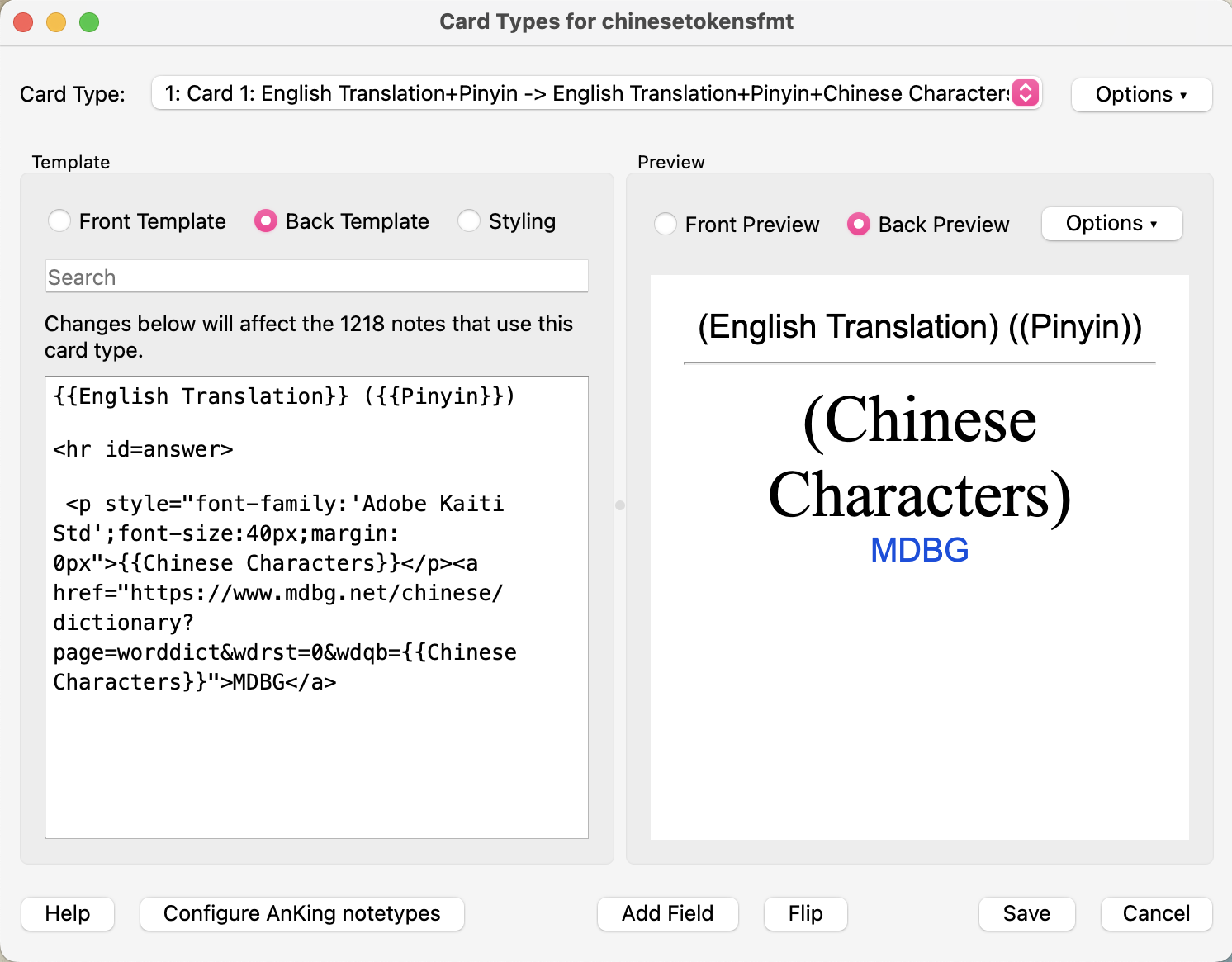

The back of the card. I keep the English and pinyin visible, and then also

display the Chinese characters using a more traditional font (Adobe Kaiti) so

so that it contains all the stroke details of the characters as opposed to a

sans-serif font.

The back of the card. I keep the English and pinyin visible, and then also

display the Chinese characters using a more traditional font (Adobe Kaiti) so

so that it contains all the stroke details of the characters as opposed to a

sans-serif font.

Note that the card backs contain links to the MDBG Chinese dictionary, which provides an easy way to check if I’m getting stroke order correct. With this card format, creating a new card is quite convenient. It looks like this:

And the created card in action looks like this:

Repetition is key

I don’t just add terms to my deck in isolation. For each character in a particular term I’m adding, I also add a bunch of other terms that also contain this character. For example, even though I may have only had “室内” in my list of terms to add, I actually may end up adding 5 flashcards to my deck for the character 内, e.g.

\[\begin{align} 室&\color{green}内\\ &\color{green}内\color{black}存\\ &\color{green}内\color{black}衣\\ &\color{green}内\color{black}容\\ 国&\color{green}内\color{black}外 \end{align}\](Sometimes I even go on deep tangents; for example, I might find the term 内容, realize I recognize but can’t read the character 容, and end up also adding terms for that character such as 容易.)

This has several benefits:

- It solidifies my understanding of the meanings of the words. For example, some characters may have a rather abstract meaning on their own, but are used in words in similar topics or areas. Or sometimes characters mean completely different things in different contexts.

- Sometimes characters are pronounced differently when used in different terms.

- Seeing the same character in different contexts “disconnects” the character from any particular term, enabling me to be able to read the character even in isolation.

- I get extra practice writing the same characters while I review, since I see them more often.

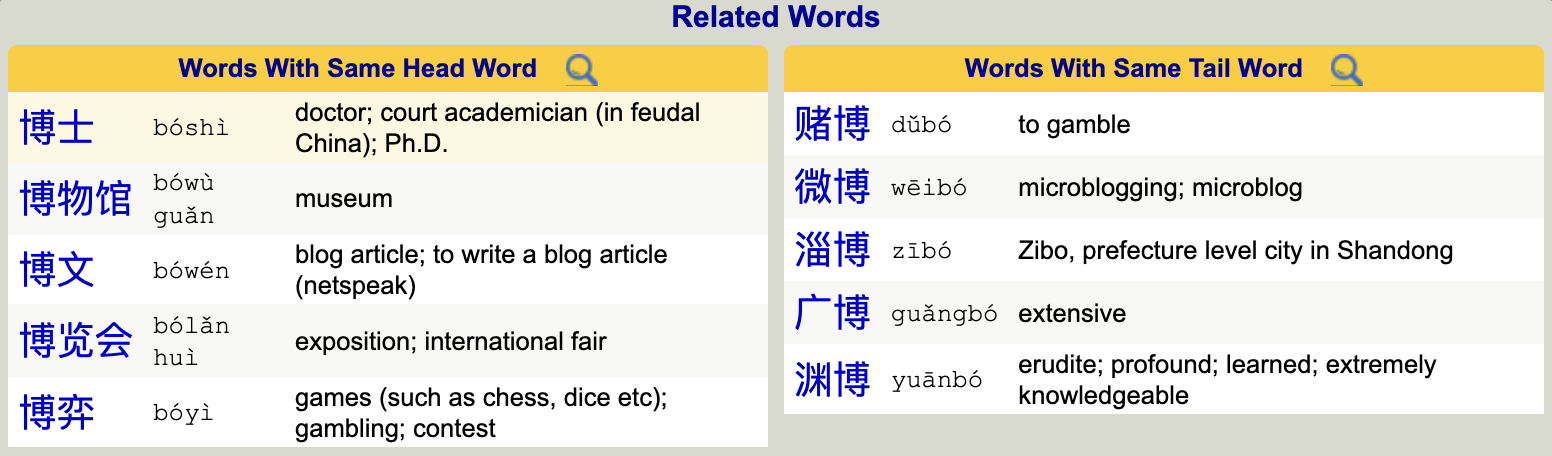

My favorite website to use when making flashcards is the Yellowbridge dictionary. Besides providing definitions and pinyin and effective pinyin tones, Yellowbridge also provides a “Related words” section that is perfect for discovering terms that contain a particular character. This makes it really easy to create flashcards that all practice a certain character.

Continuing with the 博文 example from earlier.

Continuing with the 博文 example from earlier.

I won’t add all of the related words for each character. I mainly seek out terms that I’ve heard before (but may not contain all characters that I recognize), or terms that contain all characters that I recognize (even though I’ve never heard the term before). These have somewhat opposite functionalities; one is using preexisting vocab knowledge to strengthen reading/writing skills, and the other is using reading/writing skills to strengthen vocab knowledge.

Reviewing

After the storing phase, I now have a bunch of flashcards in an Anki deck to practice with. So that’s what I do – practice. Nothing fancy here.

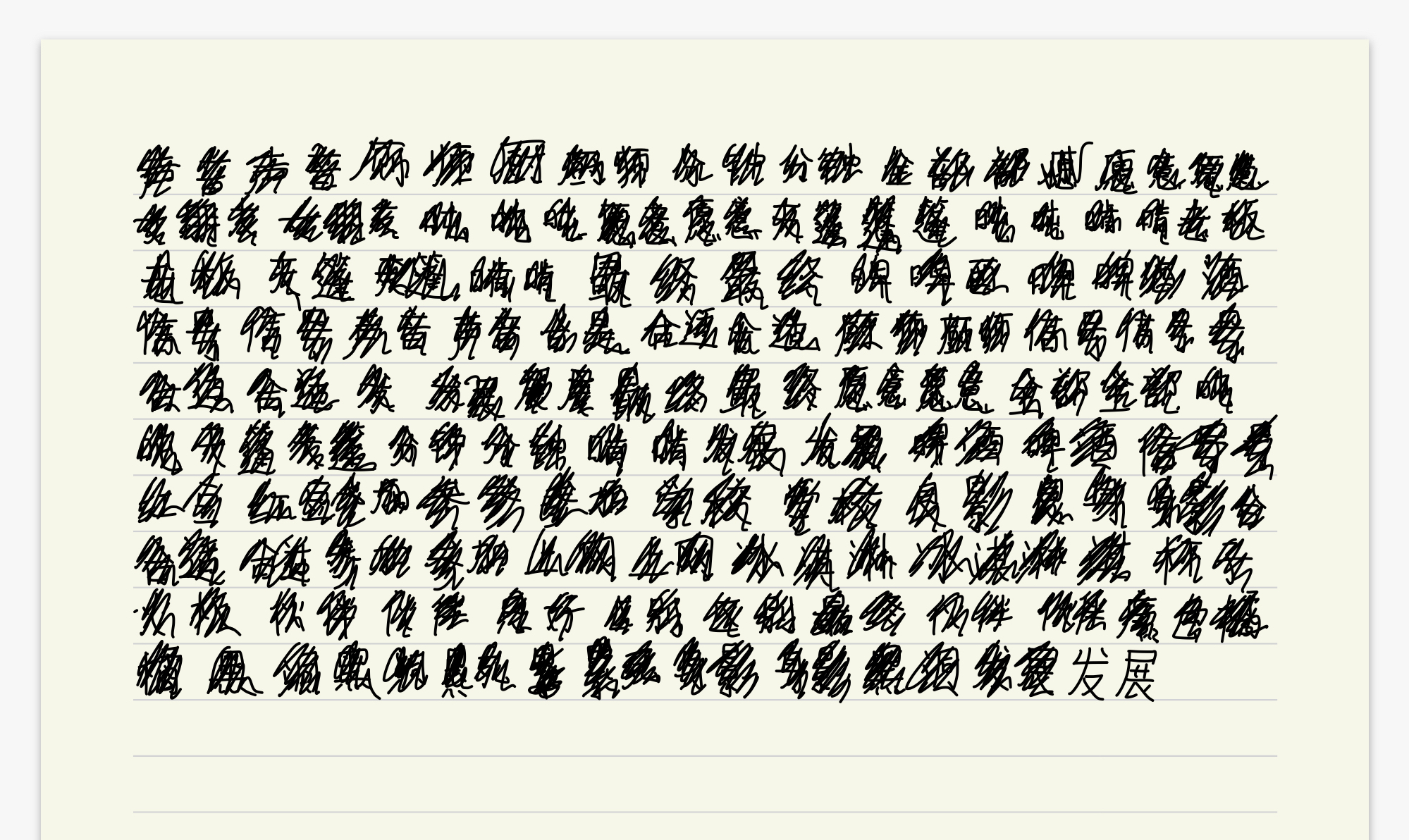

One thing to note is that studying is not a passive process. For each flashcard, I look at the front (English + pinyin), try to write out the corresponding Chinese characters, and then check my guess with the back. I just use a piece of paper and pencil when practicing, or iPad and notes app. As I go, I scratch out the character I just wrote previously, so I can’t cheat later on.

What a scratch paper looks like as I practice writing.

What a scratch paper looks like as I practice writing.

If I don’t know a character, I may write it, scratch it out, write it again, etc. until I can confidently write it from memory. Then, Anki will show it to me again in 10 minutes and I will do the same thing – exhaustively rewriting the character until I can remember it.

The good thing with Anki is that even though my flashcards deck is so large and repetitive, its never overwhelming to study; only a few cards may be due each day, and you are also rewarded for being able to recognize terms despite not seeing them for incredibly long times.

This means I can really put in a very reasonably small amount of time reviewing each day and still see good results. And although it may seem that I am only learning writing, not reading, I firmly believe the best way to learn to read something is to be able to write it yourself. Plus, I do get my reading practice in, but not during the reviewing stage. Remember the collecting stage that is also ongoing at the same time? I practice my Chinese reading while I go through articles, collecting new vocabulary to add along the way.

So to summarize, the best way I’ve found to study Mandarin Chinese is as follows:

- Collect new terms to learn by reading material in Chinese.

- Add these terms, plus a bunch of related terms using the same characters, into an Anki deck.

- Study these terms using Anki’s spaced repetition, writing out each term on a sheet of paper to test and reinforce memory.