Padding in C structs

Posted on June 1, 2023. Tags: c, systemsWhat are structs?

C doesn’t have any of the object-oriented facilities that its successors C++ or Java have, but it still provides us with an incredibly useful abstraction for tying together related data: the struct. For example, we could represent a cat with the following struct:

typedef struct cat {

int color;

int age;

double weight;

} cat;

Then, we can interact with a struct and its members like so:

cat garfield;

garfield.weight = 51.3;

printf("%d\n", garfield.age);

On a first glance, the syntax is very reminiscent of a Java class with all

public members. But structs are much more bare-bones than any Java class; rather

than inheriting tons of methods or bookkeeping functionality from a parent

Object, structs are little more than syntactic sugar over storing the

variables one after another, consecutively in memory.

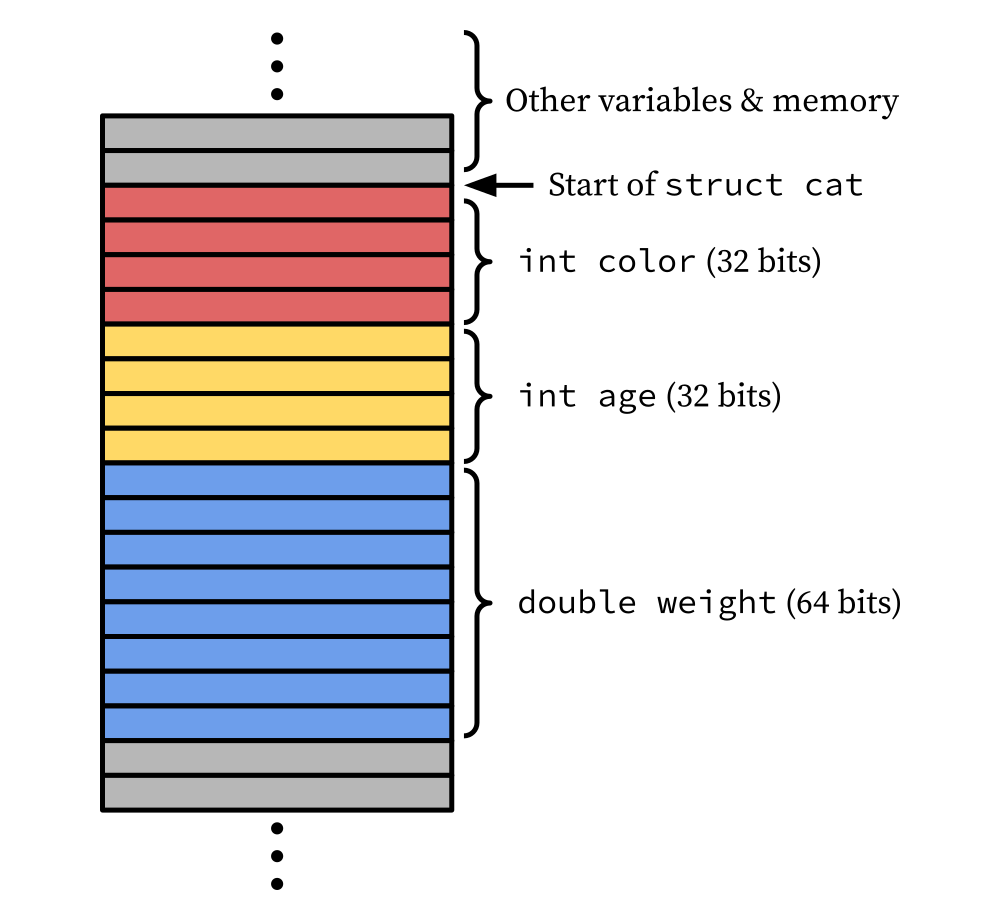

If we visualize our memory as a long tape, where each little rectangle is one

byte, a cat struct looks something like this:

Since it’s that straightforward, we can access the fields of garfield without

using the . operator, simply via pointer dereferencing. First, we load

garfield’s address into a pointer variable called garfield_ptr, like this:

void *garfield_ptr = (void *) &garfield;

color is the first field in the cat struct, which means we can access

color simply by dereferencing an int with a zero byte offset relative to

the start of the struct:

assert(*(int*) (garfield_ptr + 0) == garfield.color);

What if we want age? Well, the first four bytes of the struct are used to

store int color, so it makes sense that we can obtain age by dereferencing

an int with a four byte offset relative to the start of the struct:

assert(*(int*) (garfield_ptr + 4) == garfield.age);

And for weight? Well, you can probably guess; it starts 8 little rectangles

down from the start of the struct – the total space needed for color and

age. So we can access it like so:

assert(*(double*) (garfield_ptr + 8) == garfield.age);

From this example, we’ve seen that C structs are remarkably compact and stupid

simple. They are essentially some sweet syntactic sugar provided by the compiler

to group variables together under one name; we can use structs perfectly fine

(even without the . operator) just by working with its underlying memory

representation.

In fact, in this case, we have that the entire memory footprint

of the struct cat is equal to the sum of the memory footprints of all of its

properties; not a single byte more is needed. We have that

sizeof(cat) = sizeof(int) + sizeof(int) + sizeof(double) = 4 + 4 + 8 = 16.

Let’s now turn to a case that shows things are a bit more nuanced than it seems.

Complicating matters

Suppose we wanted to add a new field to our cat struct, one that keeps track of the cat’s first initial:

typedef struct cat {

char initial;

int color;

int age;

double weight;

} cat;

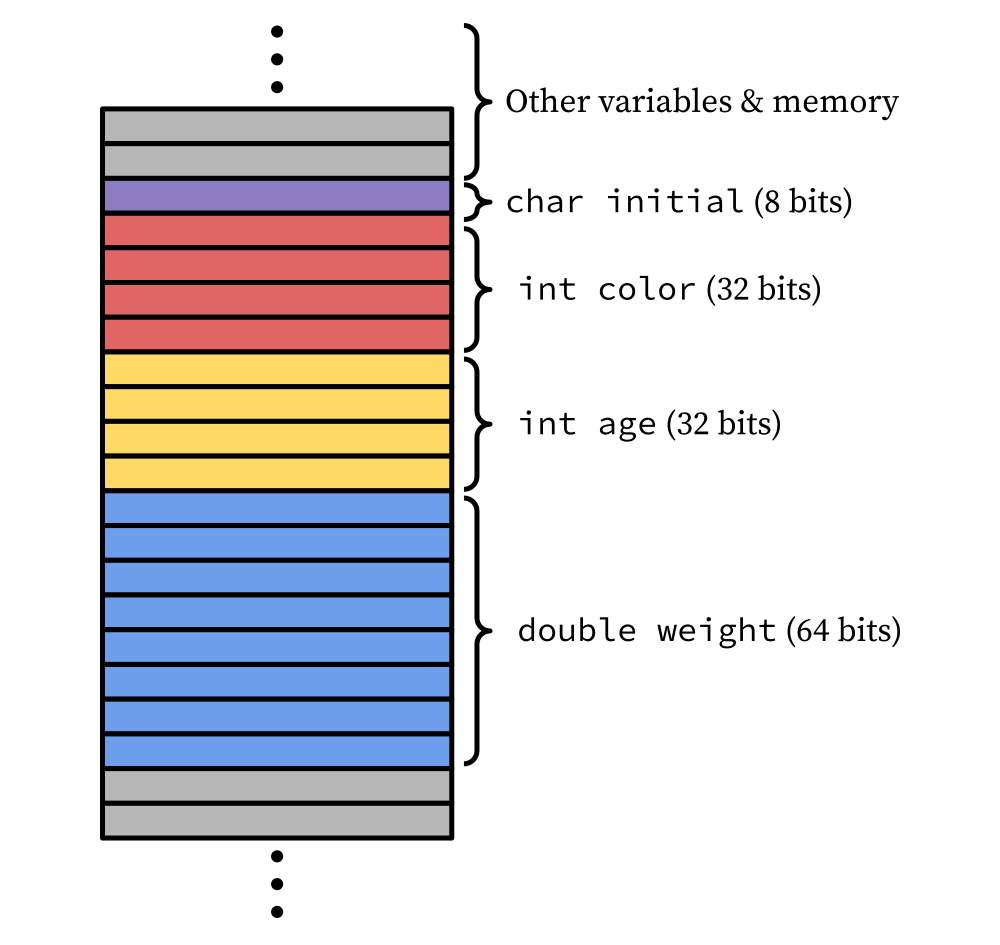

Based on our current understanding of how structs work, we might expect it to be laid out something like this in memory:

That is, if the old cat struct (before we added the initial property) had

sizeof(cat) = 16, now that we added a 1-byte char to the front of the struct

we should now have sizeof(cat) = 17.

But wait; after checking, we find out that sizeof(cat) = 24. Adding a one-byte

property increased the size of the struct by 8 bytes! Huh. That’s weird.

Let’s see if we can still access the fields of the struct using the

offset-dereferencing trick from earlier. Now, to access garfield.color, we

would expect it to have an offset of 1 byte, since it is stored after char

initial in memory.

assert(*(int*) (garfield_ptr + 1) == garfield.color);

// Assertion failed: (*(int*) (garfield_ptr + 1) == garfield.color), function main, file cat.c, line 17.

// fish: Job 1, './cat' terminated by signal SIGABRT (Abort)

This no longer works either. What’s going on here??

Tripping over chunks

It turns out that modern processors are faster at retrieving ints, doubles,

and other basic data types from memory if those data are aligned in a certain

way. This is because your CPU accesses bytes in memory not individually, but

rather in chunks (called

words). With

correct alignment, basic data types will always lie within a chunk, and they can

be loaded in a single operation. If your data is not aligned correctly, though,

the CPU may need to load a chunk and then shift the loaded data a bit to get the

desired value, or even worse it may need to load several of these chunks, shift

each one, and then use another extra operation to concatenate the two results

together to obtain the desired value.

This is so much more complicated than just loading a properly-aligned value that in fact some older processors, such as the Sun SPARC or Motorola 68k, simply do not support loading misaligned values and will throw an illegal instruction error.

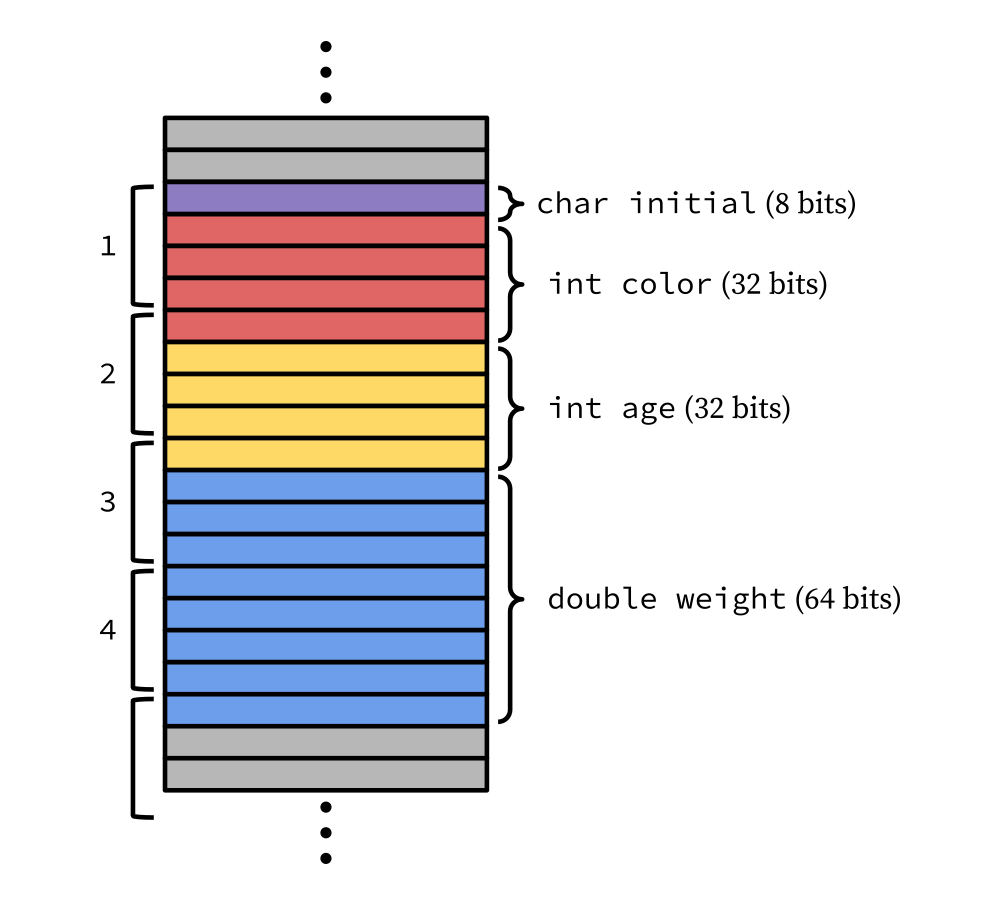

To visualize this, let’s go back to our proposed cat layout from earlier, and

assume that the computer uses a chunk size of 32 bits (i.e. it accesses 4 bytes

at a time). I’ve drawn out and numbered the chunks on the left.

Since color is not aligned to the start of a chunk, we can see that it spills

over into the next chunk; thus to access it, the CPU would need to load both

chunks 1 and 2, shift the contents of each to isolate only the bytes for color

(we don’t want initial or the part of age that gets accidentally loaded

in the process), and then combine the result together.

(Side note: this is a bit of an oversimplification, as we leave out the discussion of buses, caches, and all of the other fancy things CPUs have to make things faster. But it’s still a good intuition to have and image to keep in mind.)

This is much slower and more difficult than if color were nicer-placed in

memory. So why don’t we just do that?

Data as nature intended

Almost all CPUs are optimized to load data from memory that is naturally aligned (also known as self-aligned). What this means is that data starts at an address that is divisible by its size.

In other words, 8-byte doubles should be aligned to addresses that are

divisible by 8, and 4-byte ints should be aligned to addresses divisible by 4.

We can put 1-byte chars anywhere and they’ll be naturally aligned, since

obviously any address is divisible by 1.

With these correct alignments, loads and stores are faster and indeed more natural, since the CPU reads memory in chunks aligned to these divisibility rules, so it does not need to go through the extra logic of loading multiple chunks to piece together the data.

Compilers know this, so to optimize structs for fast access, they introduce padding around fields implicitly to make sure everything is stored according to its natural alignment.

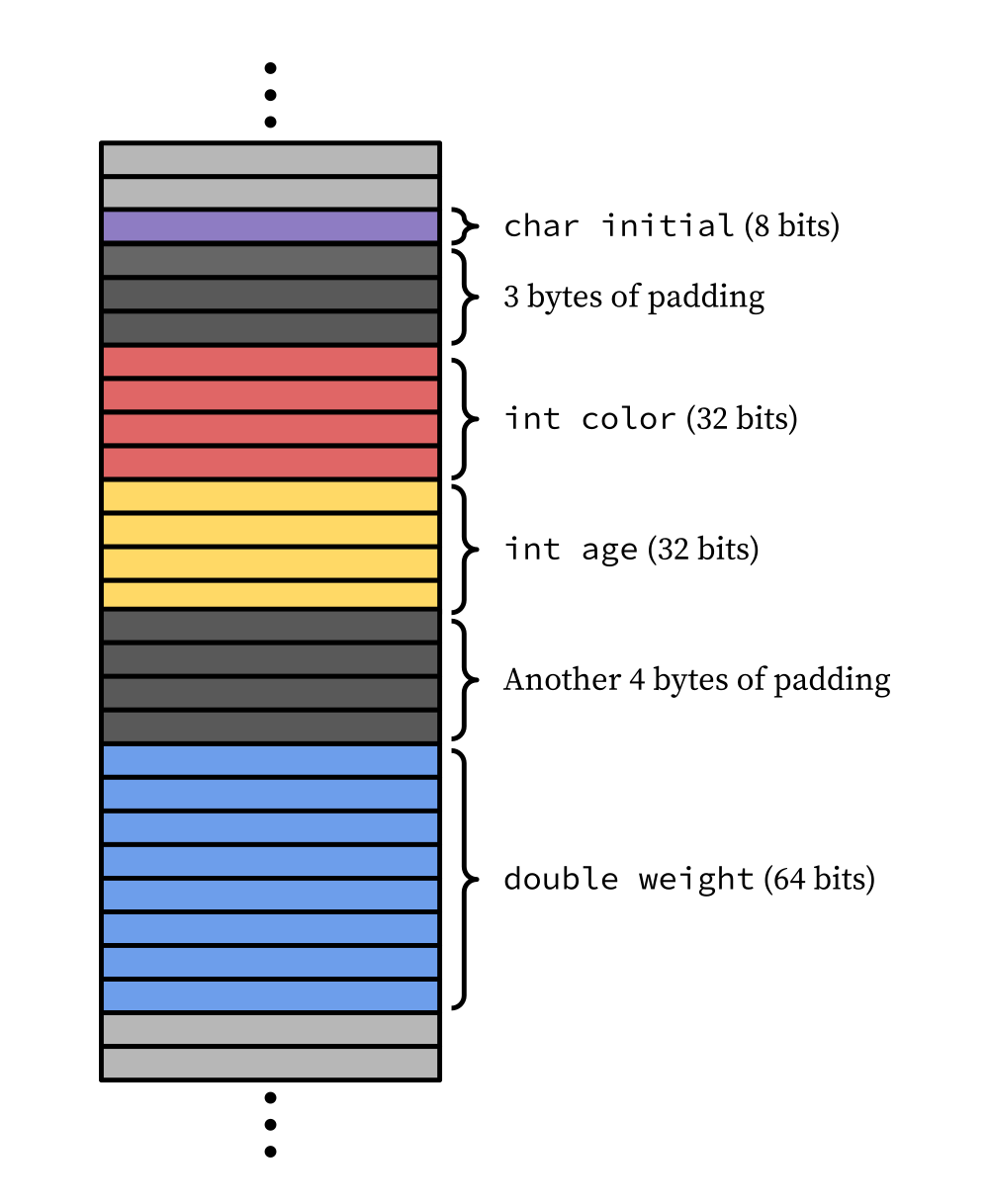

So let’s see what the cat struct actually looks like in memory:

We can see that (assuming the struct itself starts at an address divisible by 8, which it will):

initialis naturally aligned, just by nature of being achar- By including three bytes of padding,

colorstarts at an offset of 4 bytes from the struct start, so its address is divisible by 4. agestarts at the next address after the end ofcolorthat is divisible by 4. Happily,coloritself is perfectly 4 bytes, soagecan start immediately after with no padding. It is thus an offset of 8 bytes from the struct start, so its address is divisible by 4.weightstarts at the next address after the end ofagethat is divisible by 8 (note its alignment requirements are different, since doubles are 8 bytes not 4). We include 4 bytes of padding beforeweightso that it starts at an offset 16 bytes from the struct start, so its address is divisible by 8.- The total memory footprint of the struct is 24 bytes, which matches up with

the value reported by

sizeof(cat). - The whole struct worked out to be divisible by 8, which is perfect because we

need the struct to start at an address divisible by 8 (suppose we had an

array of

catstructs; then each element of the array needs to start at an address divisible by 8). If it didn’t work out so well, we would have had to add padding at the end to make it the right size.

And our offset-dereferencing trick earlier for accessing struct values simply

with a pointer starts working again, now that we know the actual placement of

color in memory to be an offset of four bytes, not 1:

assert(*(int*) (garfield_ptr + 4) == garfield.color);

// Works!

Packing more tightly

It turns out we can’t do better with the cat struct from above, but let’s

look at another example. Consider the struct below:

struct test {

char a;

int b;

char c;

double d;

int e;

char f;

};

Without reading further, try to guess what sizeof(struct test) will be.

Remember, all properties need to be naturally aligned, and the size of the

struct itself needs to be an appropriate size so that if we were to store a

bunch of struct tests consecutively in an array, each struct would start at an

address divisible by what we need it to be.

…

If you guessed 32, congrats! If not, here’s the same struct, except now with all of the padding written out explicitly. You can check yourself that all properties in the struct are aligned correctly (assuming the struct starts at an address divisible by 8), and that total space usage is 32 bytes.

struct test {

char a;

char pad1[3];

int b;

char c;

char pad2[7];

double d;

int e;

char f;

char pad3[3];

};

There’s quite a lot of padding in there, and we really could do a lot better.

For example, consider this new version of struct test, which contains all

of the same properties of the former, just listed in a different order:

struct test {

char a;

char c;

char f;

int b;

int e;

double d;

};

This basically equivalent struct now uses 24 bytes. Here it is, with padding written out:

struct test {

char a;

char c;

char f;

char pad1[1];

int b;

int e;

char pad2[4];

double d;

};

The previous struct test contained 13 bytes of filler padding; now, it only

contains 5 bytes. We’ve saved 8 bytes of space – a whopping 25% decrease. Sure,

8 bytes is negligible nowadays, but imagine this scaled up across millions of

such struct tests; it could reduce memory usage from 64GB to 48GB, which is

nothing to laugh at. And the effort on our part is absolutely minimal.

So be mindful of how you order fields in a struct! It matters.

Want to pack even more tightly, i.e. get rid of the padding completely? Your

compiler probably has an option for you to tell it to stop adding padding you

didn’t ask for; with gcc, you can do so by adding an attribute to the struct

declaration, like so:

struct __attribute__((__packed__)) test {

char a;

char c;

char f;

int b;

int e;

double d;

};

And with this, sizeof(struct test) is now 19 bytes. Keep in mind this space

savings comes at a performance cost, since now your data is misaligned; your

CPU will have to jump through some hoops to retrieve and store data.

Appendix: Is misaligned access really slower on latest processors?

When writing this blog post, I wanted to see if I could quantifiably measure how much slower working with misaligned data is. I wrote this sample C program, which tests reads and writes to a struct which I could compile as either packed or not packed.

#ifdef SHOULD_PACK

#define PACK __attribute__((__packed__))

#else

#define PACK

#endif

struct PACK test {

char c;

int height;

double weight;

};

int main() {

struct test t[1000];

for(int i = 0; i < 1000000000; i++) {

int q = i % 1000;

t[999 - q].height = (int) t[q].weight;

}

}

And indeed, the binary compiled with -DSHOULD_PACK does run slower, according

to my benchmarks:

$ hyperfine --warmup 3 './packed' './notpacked'

Benchmark 1: ./packed

Time (mean ± σ): 1.290 s ± 0.004 s [User: 1.286 s, System: 0.003 s]

Range (min … max): 1.286 s … 1.299 s 10 runs

Benchmark 2: ./notpacked

Time (mean ± σ): 1.248 s ± 0.001 s [User: 1.245 s, System: 0.003 s]

Range (min … max): 1.247 s … 1.251 s 10 runs

Summary

'./notpacked' ran

1.03 ± 0.00 times faster than './packed'

For practical purposes, this is already enough to correctly say that “Packing C structs will cost you performance by making your compiled binaries slower”.

However, is this truly due to misaligned access? Here’s the assembly generated

by gcc-13 -Wall test.c -DSHOULD_PAD -S:

.arch armv8-a

.text

.align 2

.globl _main

_main:

LFB0:

mov x12, 16016

sub sp, sp, x12

LCFI0:

str wzr, [sp, 16012]

b L2

L3:

ldr w0, [sp, 16012]

mov w1, 19923

movk w1, 0x1062, lsl 16

smull x1, w0, w1

lsr x1, x1, 32

asr w2, w1, 6

asr w1, w0, 31

sub w2, w2, w1

mov w1, 1000

mul w1, w2, w1

sub w0, w0, w1

str w0, [sp, 16008]

ldrsw x0, [sp, 16008]

lsl x0, x0, 4

add x1, sp, 16

ldr d0, [x1, x0]

mov w1, 999

ldr w0, [sp, 16008]

sub w0, w1, w0

fcvtzs w2, d0

sxtw x0, w0

lsl x0, x0, 4

add x1, sp, 12

str w2, [x1, x0]

ldr w0, [sp, 16012]

add w0, w0, 1

str w0, [sp, 16012]

L2:

ldr w1, [sp, 16012]

mov w0, 51711

movk w0, 0x3b9a, lsl 16

cmp w1, w0

ble L3

mov w0, 0

add sp, sp, x12

LCFI1:

ret

LFE0:

.section __TEXT,__eh_frame,coalesced,no_toc+strip_static_syms+live_support

EH_frame1:

.set L$set$0,LECIE1-LSCIE1

.long L$set$0

LSCIE1:

.long 0

.byte 0x3

.ascii "zR\0"

.uleb128 0x1

.sleb128 -8

.uleb128 0x1e

.uleb128 0x1

.byte 0x10

.byte 0xc

.uleb128 0x1f

.uleb128 0

.align 3

LECIE1:

LSFDE1:

.set L$set$1,LEFDE1-LASFDE1

.long L$set$1

LASFDE1:

.long LASFDE1-EH_frame1

.quad LFB0-.

.set L$set$2,LFE0-LFB0

.quad L$set$2

.uleb128 0

.byte 0x4

.set L$set$3,LCFI0-LFB0

.long L$set$3

.byte 0xe

.uleb128 0x3e90

.byte 0x4

.set L$set$4,LCFI1-LCFI0

.long L$set$4

.byte 0xe

.uleb128 0

.align 3

LEFDE1:

.ident "GCC: (Homebrew GCC 13.1.0) 13.1.0"

.subsections_via_symbols

Most of this output is GCC blabber and is rather ignorable, but what is of note

is the movks, the lsrs, and that GCC never calls str or ldr with an

odd (or even not divisible by 4) offset. This is indicative that GCC is

generating instructions itself to avoid misaligned reads and writes, and is

doing the whole shifting + piecing together data on the instructions side,

rather than letting the chip do it.

So the slowdown is due to these extra movks and additional logic, rather than

really str or ldr-ing from a misaligned address. To try to go a bit deeper

and get around this, I wrote the below Assembly program to see if reading and

writing from strange addresses is slower, but did not see any difference

between packed vs. non-packed writes in my benchmarks:

.global _main

.align 2

_main:

SUB SP, SP, #32

MOV X0, 0

MOV X3, #1

LSL X3, X3, #30

LOOP:

CMP X0, X3

B.GE ENDLOOP

#ifdef SHOULD_PACK

LDR X1, [SP, 3]

ADD X1, X1, #1

STR X1, [SP, 11]

#else

LDR X1, [SP, 8]

ADD X1, X1, #1

STR X1, [SP, 16]

#endif

ADD X0, X0, #1

B LOOP

ENDLOOP:

ADD SP, SP, #32

MOV X0, #0

RET

Unfortunately, I think this is more symptomatic of other CPU features (especially caching) getting in the way of my tests than it is proving that misaligned reads and writes are just as fast as their aligned counterparts. To get around that, we’d need to write a bit more complicated program.

I’m a bit tired of writing assembly, so I won’t pursue this. But it’s definitely an avenue of exploration for later, and also a learning opportunity for me to solidify my knowledge of caches, buses, and the likes.