Packing spheres in leaky boxes

Posted on May 23, 2023. Tags: math, geometryJust a curious, rather counterintuitive result I came across recently.

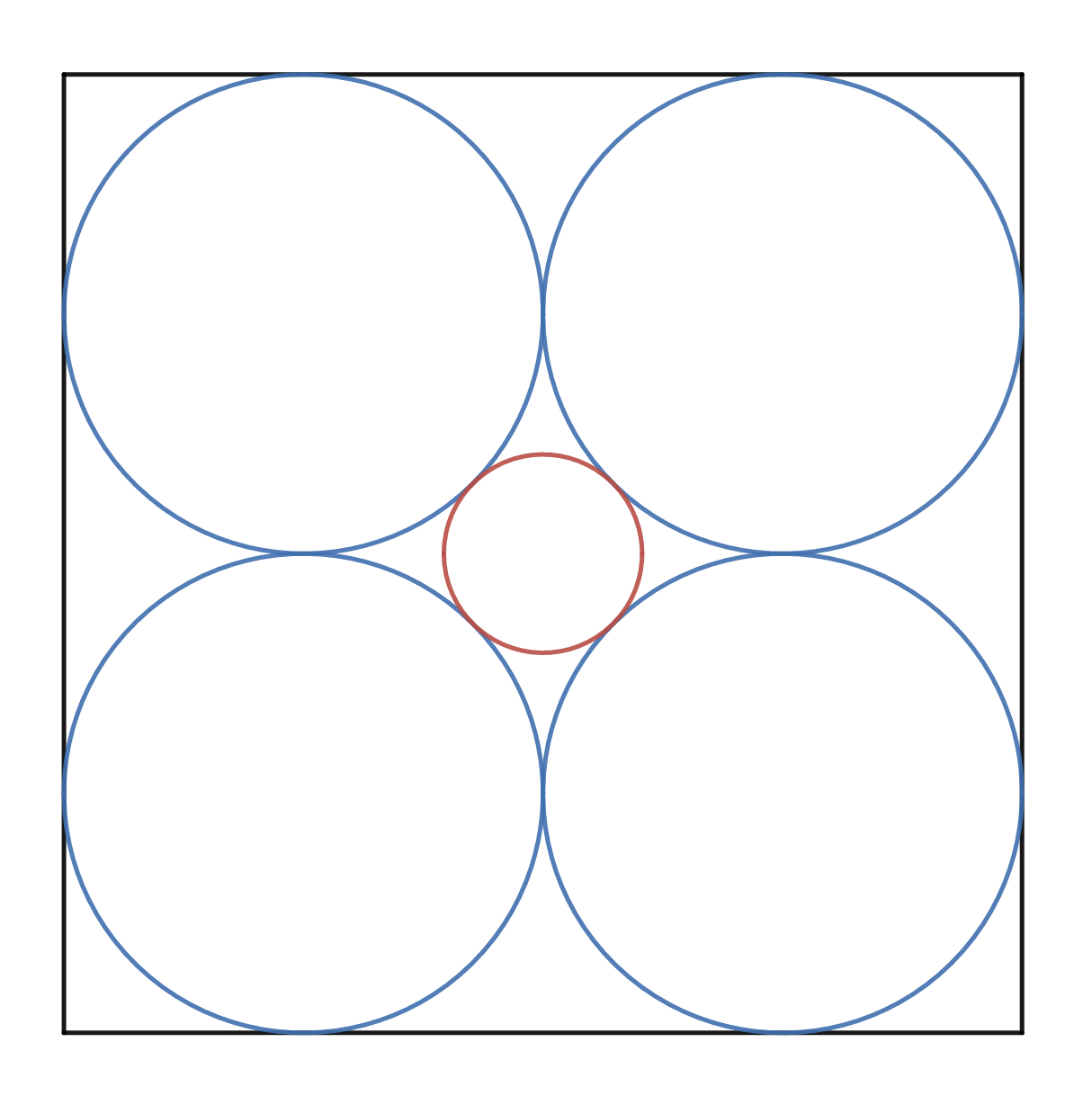

Let’s imagine we are working in the 2d plane for the time being. We start with a \(1\times1\) unit square (black).

Into the square, we first pack 4 circles of diameter \(\frac{1}{2}\) (blue). Finally, in the open space right in the center of those 4 circles, we place one more circle, as big of a radius as we can fit (red).

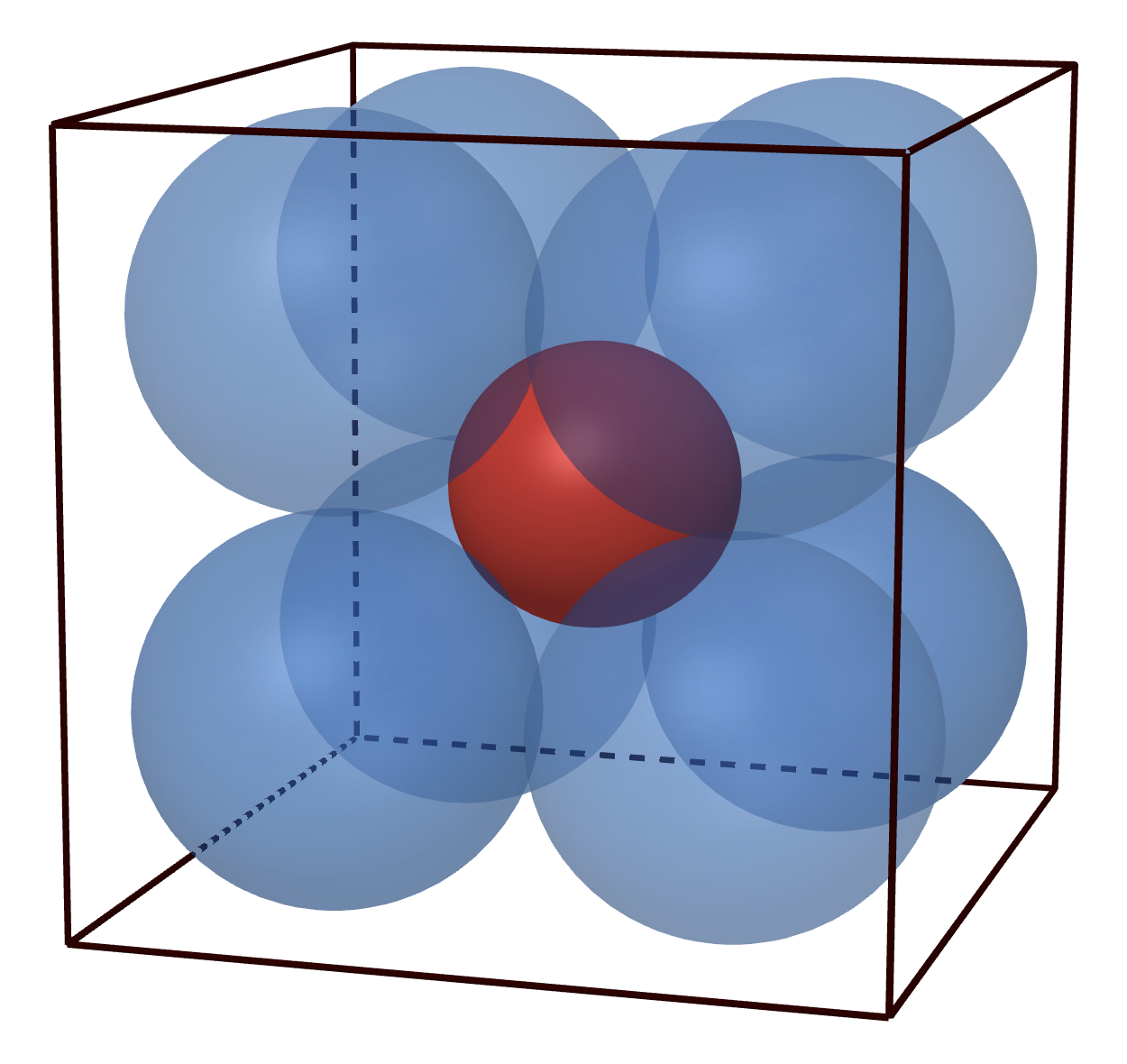

It’s obvious that the red circle is totally contained inside the black square. And we can extend this to three dimensions as well; now, we consider a \(1\times 1\times 1\) box, and we place eight spheres of diameter \(\frac{1}{2}\) inside. In the middle, we pack one more red sphere, as big as we can make it, so that it is touching all eight of the blue spheres:

And still, like packing a basketball in bubble wrap, we see that the red sphere is totally contained within the cube.

We can even extend this into higher dimensions - it just becomes mildly impossible to visualize. In four dimensions, we would place sixteen 4d hyperspheres into a unit tesseract. In general, for dimension \(d\), we fill the \(d\)-cube with \(2^d\) hyperspheres, each of diameter \(\frac{1}{2}\). Then, we place one more hypersphere right in the center of the \(d\)-cube (that is, centered at \(\left(\frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{2},\dots,\frac{1}{2}\right)\)), with a radius as large as possible so that it is tangent to all of the other spheres.

An interesting question to ask is, what’s the diameter of the circle in the 2d case? And can we come up with a general formula that gives us the diameter of the sphere in any \(d\)-dimensional space?

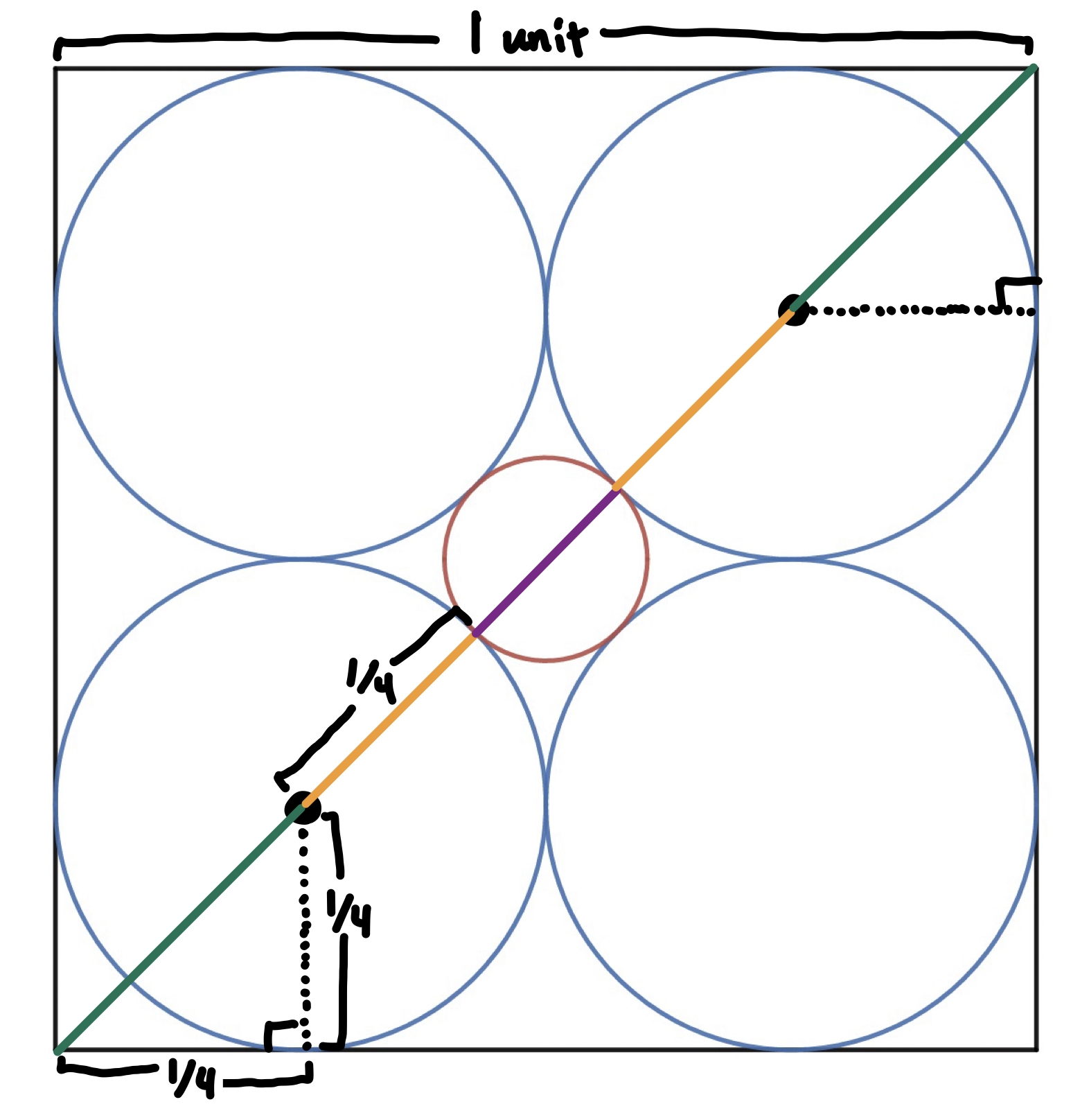

The answer is yes, with some fairly straightforward, grade-school geometry. Let’s focus on the 2d case for now; we draw a diagonal line connecting \((0,0)\) and \((1,1)\), and break it up into five segments:

The length of the whole diagonal is just the distance between \((0,0)\) and \((1,1)\) – using the distance formula, that’s just \(\sqrt{(1-0)^2 + (1-0^2)} = \sqrt{1+1} = \sqrt{2}\). The green segments, extending from the corners of the square to the centers of the nearby circles, are hypotenuses of right triangles as well, this time with leg length \(\frac{1}{4}\). Thus they have length \(\color{green}\frac{\sqrt{2}}{4}\). The orange segments extend from the center of the circle to the edge, and so are just radii of circles with diameter \(\frac{1}{2}\); thus the orange segments have length \(\color{orange}\frac{1}{4}\). Finally, the length of the purple segment – the diameter of the red circle – is what we are trying to find; let’s call it \(\color{purple}x\).

Putting it all together, we have the total length of the diagonal is equal to the sum of its segments: that is,

\[\begin{align} \sqrt{2} &= \color{green}\frac{\sqrt{2}}{4}\color{black}+\color{orange}\frac{1}{4}\color{black}+\color{purple}x\color{black}+\color{orange}\frac{1}{4}\color{black}+\color{green}\frac{\sqrt{2}}{4}\\ &= \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} + \frac{1}{2} + x\\ \implies x &= \sqrt{2} - \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} - \frac{1}{2}\\ &= \frac{\sqrt{2}-1}{2}\\ &\approx 0.2071067811865475244... \end{align}\]This result makes sense; roughly eyeballing our diagram, the red circle’s diameter does indeed appear to be just a bit less than the radius of one of the blue circles.

Note that since the diameter is less than 1, we’ve proven that the red circle lies squarely within the containing square, since the square has height 1.

We can easily extrapolate this to three dimensions and onwards. For any higher dimension, we again draw a diagonal from \((0,0,\dots,0)\) to \((1,1,\dots,1)\) and break it into five segments. What’s the length of the diagonal now? The distance formula in higher dimensions is just

\[\sqrt{(x_1-x_2)^2 + (y_1-y_2)^2 + (z_1-z_2)^2 + \cdots}\]I won’t prove this here, but if it’s not obvious to you, I leave it as an exercise for you to prove it in three dimensions; first find the distance from \((x_1,y_1,z_1)\) to \((x_2,y_2,z_1)\) using the normal 2D distance formula (ignoring the \(z\)-coordinate). Then, recognize that you can form a right triangle with the points \((x_1,y_1,z_1)\), \((x_2,y_2,z_1)\), and \((x_2,y_2,z_2)\); use the Pythagorean theorem to then find the distance between \((x_1,y_1,z_1)\) and \((x_2,y_2,z_2)\).

Applying this distance formula to our two points \((0,0,\dots,0)\) to \((1,1,\dots,1)\), we get

\[\begin{align}&\sqrt{(1-0)^2 + (1-0)^2 + (1-0)^2 + \cdots}\\ =&\sqrt{1+1+\cdots}\\ =&\sqrt{d}.\end{align}\]The length of the green segments also change, for the same reason; as you might guess, instead of \(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{4}\), they now have length \(\frac{\sqrt{d}}{4}\). But the length of the orange segments are still the radii of the blue spheres, which remains \(\frac{1}{4}\).

So now we have everything we need to find the diameter of \(x\) in any higher-dimensional space \(d\). We use similar algebra as before:

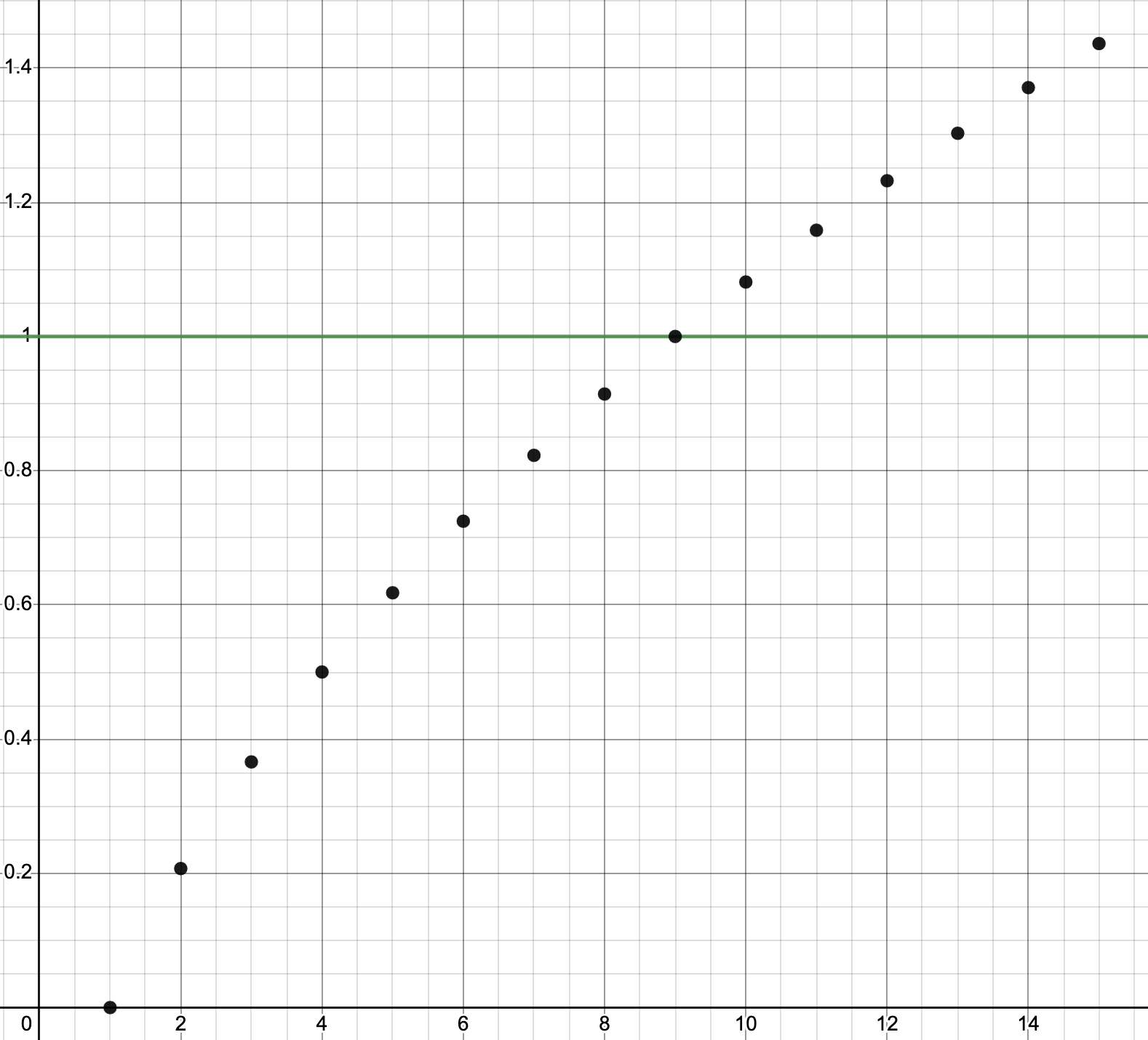

\[\begin{align} \sqrt{d} &= \frac{\sqrt{d}}{4}+\frac{1}{4}+x+\frac{1}{4}+\frac{\sqrt{d}}{4}\\ \implies x &= \sqrt{d} - \frac{\sqrt{d}}{2} - \frac{1}{2}\\ &= \frac{\sqrt{d}-1}{2}. \end{align}\]Plugging in \(d=2\), we see that we get the same result as earlier. For \(d=3\), we find that the diameter of the red sphere is \(\frac{\sqrt{3}-1}{2}\approx 0.366\). In fact, we can make a plot where the \(x\) axis is increasing values of \(d\), and the \(y\) axis is the diameter of the red ball. (I’ve also drawn a horizontal line at \(y=1\).)

As we can see, the diameter of the red ball increases as the number of dimensions increases. But wait a minute; it keeps increasing, past the line representing a height of 1!

What we’ve found is that in 9-dimensional space, the red sphere actually touches the sides of the box. And in dimensions higher than 9d, the red sphere actually leaks out of the sides of the box; its diameter is greater than the height of the box.

Despite the red sphere being packed within and surrounded by blue spheres that cover all sides of the cube and are fully contained within the cube, the red sphere itself is not necessarily contained within the cube. This behavior is not something I would have guessed, with my 3d world intuition.

So, if you want to mail a 10-dimensional basketball to your friend in a 10d cardboard box, be careful about how you bubble-wrap it; it may just leak out.